Slams and sonatas

Angela Dickson is both a translator and a musician. And there are quite a few parallels between the two, she explains

Picture the scene… a translator at work. Cinematic, no? A lone figure, sitting at a desk (an ergonomically impeccable set-up, of course), grappling with words in silence, occasionally scratching their head, looking things up, maybe reaching for the odd reference book. If you wait long enough, they might phone a colleague or start a Zoom call.

Admittedly, this is perhaps not a recipe for the greatest film ever made. But can translators perform? Of course we can – though we may be afraid to. The translation slam might be more a spectacle for those already in the profession, or for those with a serious interest, but there is a lot to be gained from this public display of how we work.

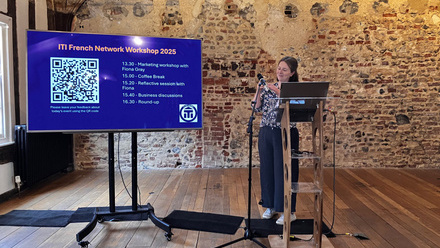

I took part in a translation slam in June 2023, part of the ITI French Network’s very enjoyable 35th-anniversary event in Birmingham (see Mike Hanson’s write-up on page 41 for a full description). At the time it felt like stepping into a very unfamiliar zone, particularly as I was ‘slamming’ a text that was very far from my usual medical translation, but the more that I reflect on it, the more similarities I see with my other life (I can’t even use the young person’s term ‘side hustle’, since it isn’t lucrative) as a performing musician.

The translating performer

Since I was a child I have always played in some musical group or other. My area is classical music, and as I don’t improvise, my responsibility is to translate (see what I did there?) the music from the dots on the page into something a listener can appreciate, getting in the way as little as possible. For every piece of music, there are as many ways to perform it as there are performers and performances, as we have wildly different experiences, backgrounds and even ideas about how to shape phrases. Sound familiar? Of course it does, since there are as many different translations of a given text as there are translators.

Earlier this year I performed a double concerto (two soloists stand at the front) with my regular orchestra. It was quite an experience. The orchestra is full of friends I have known for years and has a fantastic conductor whom I trust implicitly. That kind of supportive community is a delight when you’re stepping up to perform solo; and having a fellow soloist was also wonderful, since the limelight felt less glaringly bright. I prepared my part as well as I could, with the help of my occasional teacher.

I do get nervous, but it’s the ‘excited’ kind of nerves, rather than the type that inhibit performance (even some professional players experience those, and I’m told beta blockers are commonly used in the business). On performance day all I could do was just go for it and hope that any blemishes were compensated for by the shape and effect of the whole.

Technique and peer review

The common thread here is technique: the nuts and bolts of how to use your body to produce sound from an instrument, or how to harness your linguistic skill to produce a piece of target language writing that reads well and reflects the source accurately. That takes time and effort to hone.

For music, which is a hobby for me, it means as many hours in the practice room as I can manage, in pursuit of specific goals. It also means occasional input from a high-level teacher, who has played the instrument for a living for many years and can show me some of the shortcuts he has learned.

For translation, technique consists of the intricacies of conveying meaning between languages; not just knowledge of both languages, but the metalinguistic knowledge that enables us to justify our choices, and the ability to convey to clients the value we add to the process, without blinding them with science. These skills are honed during our studies, on the job and with the feedback we get along the way, and can be further refined by sharing experiences with colleagues, for instance in revision clubs, accountability groups and formal workshops.

And what of theory? My music theory knowledge is not what it might be, but it’s possible to pick up a lot from years of playing with people who do know the theory. In translation, theory might not form part of your day-to-day work, but having a thorough understanding of why you work as you do is essential. We all have our own theories of translation, regardless of whether or not we can articulate these.

The goal is to hide the amount of work that goes into learning and refining technique, to reveal the (literal or figurative) music that lies beneath. I believe that is as true for the most technical of medical texts and the simplest of melodies as it is of high-flown literature and complex art music. In both translation and musical performance, a satisfactory outcome is a creation that is coherent – and that works on its own terms.

Audiences and imperfection

Have I ever produced the perfect translation? No, I have not. Have I ever done the perfect performance? Again, no. The translation, though, has a longer life than the performance – at least, the live performances I do. (My orchestra is strictly ‘live only’ so we don’t have to worry about our blemishes living forever on YouTube.) Mistakes in translations, though, live on. For a published translation that has been through editing, I am comfortable with this; for a slam text that was my best effort in an unfamiliar field, I’m less happy to have my imperfections ‘out there’, but life goes on…

Before I took part in one, I thought a translation slam would be a solo performance by the translators, but in reality it was more like a collective editing performance by a group of people who are all capable of doing the job. The audience is far more involved and has a far higher skill level than the average classical music audience (though a concerto performer’s audience includes the orchestra behind you, who may or may not think they can do it better than you). However, the audience does still play a huge role in a concert, so that concerts are always different from rehearsals – and usually better and more exciting. I often find myself playing in entirely new ways, responding to the heightened atmosphere around me and what I see and hear, and I never tire of this spontaneity built on a foundation of experience.

Ultimately, the human element is why we do what we do – it’s why we persist as human translators despite the rise of the machines; it’s why we don’t consume all our music as MIDI tracks; it’s why we go to concerts and gigs; and it’s why we attend translation conferences and slams.

It’s why we don’t do all meetings on Zoom, much as it is cheaper and more convenient to do so. It’s why so many of us felt the loss of in-person conferences and rehearsals so much during lockdown, and it’s why live events of all kinds, from conferences to concerts, came roaring back as the Covid threat receded. Making mistakes in public is scary, but if we don’t sometimes fail, we’re not trying, and I personally plan to keep on trying for as long as I have life left in me.

Never miss another Bulletin article

If you would like to read more features and articles on a wide variety of subjects relating to all aspects of the translation and interpreting industry, subscribe to ITI Bulletin. Alternatively, join ITI and get a free subscription included in your membership.