Knit two together

Anne de Freyman has been knitting since childhood. And then her dream translation project came along…

Nothing woolly about this: consistency of terminology was paramount

What do Meryl Streep, Ryan Gosling, Michelle Obama, Russell Crowe, Sir Patrick Stewart, Audrey Hepburn, Robin Williams and Kate Middleton have in common? They are, or were, all knitters. As a pretty obsessive knitter myself (it really is so good for the soul!), I was tickled pink seeing Michelle Obama on the cover of the US magazine Vogue Knitting and reading her words about the power of knitting in The Light We Carry. She learned to knit in order to deal with the havoc wreaked by the pandemic, and she says that knitting ‘buckled my churning brain into the back seat and allowed my hands to drive the car for a while. It detoured me from my anxiety, just enough to provide some relief’. She’s put into words what I felt and did around the time of the Brexit referendum.

Whereas Michelle Obama taught herself to knit in 2019, I learned with my two grandmothers – I am so grateful to them both – when I was about eight years old. I’ve knitted on and off all my life, but very much off for over a decade. Brexit, however, is the exact time when my deeply wounded soul (no exaggeration) turned instinctively to needles and yarn. Don’t ask me why ‘instinctively’ – I don’t know – but a lot of column inches have been written recently about the healing power of knitting. Maybe Michelle Obama and Tom Daley have something to do with it.

Casting on and finding a whole new universe

I discovered a whole universe that I didn’t know existed. The knitting world had developed while I was busy doing other things. I thought I knew it all but realised there was so much more to learn. New techniques, new fibres, new types of needles, websites and blogs galore – not to mention vibrant online communities, very much like the ones we know as translators. Of course, I was hooked and I have been knitting for England (and France!) ever since, striving for yarny perfection with every project.

Needless to say, I’m forever finding new parallels to draw between my career as a translator and my knitting journey. That realisation that I still had so much to learn after decades of practice was definitely not unlike what I felt the first time I attended a ‘Translate in’ event, which triggered my hunger for specialist events, even if it means going all the way to Quebec!

Carrying it over into translation

Would you believe, though, that having said all that, translating about knitting never crossed my mind? Until, totally serendipitously (although with a bit of help from the app then known as Twitter), I found myself doing a sample translation for a French publishing house specialising in crafts. The project was no less than a French translation of the 350-page Vogue Knitting – The Ultimate Knitting Book, now to be known as La grande encyclopédie du tricot.

Anne and her colleague decided to address the reader directly

In a nutshell, this volume contains everything you could possibly wish to know about knitting, from types of fibres (did you know there are yarns made of milk protein?) and needles (glass knitting needles, really?), to every stitch and technique from American English (you say stockinette, I say stocking stitch; you say seed stitch, I say moss stitch) into French, including a glossary of knitting terms and abbreviations. A big, beautiful coffee table-style book – dizzyingly exciting and daunting in equal measure. On the less daunting side, there would be two translators doing one half each and the best part of six months to complete the work.

It dawned on me, while I was working on the sample translation, that most of my knitting knowledge, however advanced, was acquired in English. The first step, once the contract was signed, was to completely immerse myself in French knitting content. I signed up to all the newsletters and blogs I could find, ordered all the books I thought I’d need – as an aside, you cannot underestimate the joy of ordering a pile of knitting books as a genuine business expense – and picked a few projects to knit from French patterns during those six months. It was the other way round for my co-translator, so we complemented each other perfectly in that respect.

Purls of wisdom

In addition to the deadline, the publisher gave us three instructions.

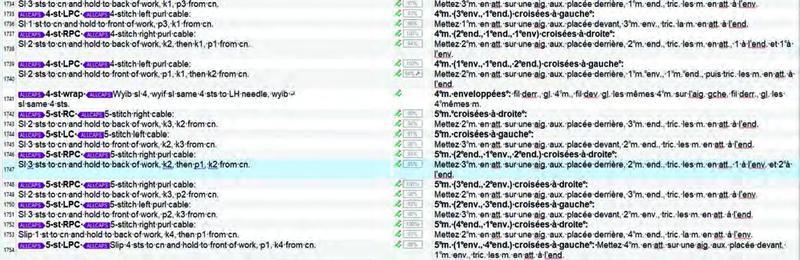

The first was to ensure consistency of terminology between our respective parts. We set up a shared Excel file, and every day we each added the terms that we’d researched or opted for, for information or discussion. There was discussion most of the time because standardised knitting terminology is rather limited outside the basics, and it’s very much a free-for-all, with no two books using the same terms, as we soon found out. I’m exaggerating, but only a little. Something as simple as ‘circular knitting’ for example, can be tricot en rond or tricot circulaire. Something more complex, like ‘stranded colourwork’ (most people will know this as Fair Isle) can be jacquard Stranded, jacquard à fils suivis or jacquard à fils flottants.

Instruction number two was ‘keep the French the same length as the English’. That’s when I panicked. French is longer than English at the best of times, but in the language of knitting, even the abbreviations are much longer. Think of ‘knit 1 purl 1’, which is abbreviated as ‘k1 p1’; or even just of ‘knit’, which becomes ‘k’ in English. The shortest French for ‘k1’ is 1 m. end. and the shortest for ‘p1’ is 1 m. env., meaning ‘k1 p1’ becomes 1 m end., 1 m. env. – so when you have a short caption explaining how to knit a specific stitch under an illustration, with very limited space, you’re in trouble. As if ‘k1 p1’ wasn’t enough of a headache, ‘knitwise’ translates as comme pour tricoter à l’endroit. Even abbreviated to comme pour tric. à l’end., it’s painfully too long. ‘K2tog’, which means ‘knit 2 together’ cannot be any shorter than tric. 2 m. ens. à l’end. And the list goes on. In a descriptive text, you can get rid of superfluous text in the source and condense the French that way, but when all you have in the English is abbreviated gobbledygook like ‘Sl 2 sts to cn and hold to back of work, k1, then p2 from cn’, there isn’t that much you can cut out. On most pages we were thankfully able to use a little bit of leeway where there was some blank space at the end of a caption and replace ‘and’ with a comma, get rid of ‘then’, etc. Where that wasn’t possible, instructions were shortened as much as we could. Thankfully too, we never had to waste time counting characters as we were both working with a CAT tool (Studio in this instance) laid out in two columns of equal width. Invaluable!

La grande encyclopédie du tricot contains everything you might possibly want to know about knitting, including every single stitch and technique.

Which brings us to instruction number three: ‘use the generic masculine form’ rather than any form of inclusive language. Of course, the word ‘knitters’ cropped up a lot and I was rather surprised that the publisher expected us to use the masculine form les tricoteurs. Indeed, that’s what had been used in previous publications. To me, however, les tricoteurs conveys images of men more than any other generic masculine term I can think of due to the simple fact that knitting is so widely associated with women. On the other hand the feminine form les tricoteuses isn’t any better to my mind for the very reason that more and more men are knitters, like my dear friend Ben, who is quickly catching up with me on sock-knitting skills.

I was rattled; my co-translator was not. But we agreed to use non-gendered language (écriture épicène) wherever possible. If successful, nobody should even notice. We did, and nobody noticed! Our favourite strategy was addressing the reader directly instead of referring to ‘knitters’, since the book is all about teaching people knitting techniques. ‘Some knitters prefer wooden needles’ for example, became vous préfèrerez peut-être les aiguilles en bois. ‘Every knitter needs x’ became x est indispensable dans votre trousse à tricot (space permitting!). At other times ‘knitters’ became personnes or on. Very often the sentence was completely turned around to avoid translating the word ‘knitters’. There are enough examples for a whole article or maybe even a training webinar, so watch this space!

Also, the book is an American publication, and as such, the content was not always meaningful to non-US readers. Some types of yarn or knitting accessories (coil-less safety pins?) simply don’t exist elsewhere. Brands of synthetic yarns are different (there is a section about all the different types of synthetic yarns!). Yarn standards and labelling are different too. Some of you may be familiar with lace, 4-ply, DK and Aran weights, but maybe not so with ‘sport’ and ‘worsted’, which are not usually available in the UK. A lot of time was spent writing translator comments to that effect and finding ways to make the text match the illustrations for some of those typically American things. So much so that, in the end, the publishers decided to put ‘adapted from English by’ rather than ‘translated from English by’.

Keeping in practice – and checking accuracy

Knowledge of the subject matter was essential to make the content relevant to the readership, but also to ensure clarity and accuracy when dealing with instructions. During the whole time it took me to translate my nine chapters, I had a ball of yarn and some needles on my desk so I could check my translation by knitting it when the English instructions and/or illustrations weren’t very clear. Some of the advanced techniques that I wasn’t too familiar with, like brioche knitting, entrelac or mosaic, I had to work on twice as hard. But what fun!

Two big projects stand out in my 30-year career as a translator. The first one was the very hush-hush translation of the full script of a forthcoming James Bond film, and the second one was most definitely this one. The expression ‘tap-dancing to work’ was equally true in both cases, but as far as this translation project is concerned, I’m hoping I can make it a regular thing.

Never miss another Bulletin article

If you would like to read more features and articles on a wide variety of subjects relating to all aspects of the translation and interpreting industry, subscribe to ITI Bulletin. Alternatively, join ITI and get a free subscription included in your membership.