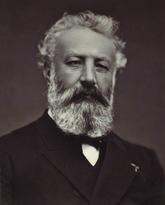

New worlds of Jules Verne

Gillian Robin explains how more recent translations of Jules Verne’s work do greater justice to a literary legend

Celebrated as a pioneer of science fiction and endlessly reprinted for a century and a half, Jules Verne is honoured as a serious literary figure in his native France – yet in the English-speaking world he has often been considered little more than a writer for children. This striking discrepancy is largely the result of the way he has been translated – and often mistranslated – into English. In fact, probably few authors have ever been so badly served by their English translators.

Travel, geography and scientific discoveries

I first discovered Verne in my early teens, when I read his classic novel A Journey to the Centre of the Earth. Like generations of readers before me, I was captivated by the story of a centuries-old coded message that leads the protagonists to descend into the crater of a volcano in an attempt to reach the centre of the globe. It’s just one of many marvellous journeys on which Verne took his readers, from the poles to the depths of the sea and even around the moon. His French publisher marketed his novels shrewdly, making them part of a consistently branded and lavishly illustrated series called Voyages extraordinaires (‘Extraordinary Journeys’).

Although he has been called the father of science fiction, most of his novels are what science fiction bibliographer Everett F Bleiler describes as ‘geographical adventures’. Verne was fascinated by travel and geography and also enjoyed reading about the latest scientific discoveries. He incorporated both into his novels, blending geography and science into adventurous exploits that took the 19th-century armchair traveller to far-flung parts of a world that had yet to be fully mapped and explored. In A Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Verne takes us on a speculative journey deep underground and at the same time educates us about contemporary geology and palaeontology. And in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, he takes his readers on an adventurous voyage around the world’s oceans while informing them about the strange new species and phenomena that were being discovered in his own time.

Inauthentic and abridged: the English versions

But what readers of the English versions did not realise was that these were far from faithful to the original novels. English translations published in the 19th and early 20th centuries – still widely reprinted and read today – were seriously flawed in many ways, from significant omissions to translation errors and outright ideological changes. As a result, English-language readers have only recently had access to the authentic Verne.

One of the main problems was abridging. The pressure to get translations into print quickly meant that the translation process was often rushed, and the obvious candidates for omission or condensing were the pages of scientific explanation and geographical or historical description. Translators tended to emphasise the adventurous elements and cut the rest – contributing to Verne’s reputation in the anglophone world as a mere genre or children’s author. Yet these pages were very important to Verne, who spent many hours in the library researching each novel to get his facts right: and indeed Verne scholar Arthur B Evans describes this ‘ubiquitous didacticism’ as a fundamental aspect of the writer’s work.

To be fair, the translator’s task was not always easy. For example, the 1872 translation Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas by Lewis Page Mercier omits many descriptive lists of marine life observed by the passengers on the Nautilus. This is fairly understandable when you realise that the original Vingt mille lieues sous les mers contains several long lists of obscure inhabitants of the deep – passages which, as David Coward ruefully says in the introduction to his 2017 translation, ‘the reader can skip, but which sorely try the translator’s patience’.

Omissions and additions: changing the original

Readers are now able to rediscover the authentic voice of Jules Verne

How important is Verne’s wealth of detail, and what is lost by omitting it? Mid-century translator IO Evans argued that the long descriptive passages would have been off-putting even to the author’s contemporaries, let alone modern readers. Yet Coward suggests that 19th-century readers would have found the ‘fish lists’ interesting because they revealed new-found knowledge about life in the oceans, while Timothy A Unwin even describes them as having a certain ‘poetic and incantatory’ quality. And commenting on A Journey to the Centre of the Earth, John Breyer and William Butcher note how Verne skilfully weaves geological information into the narrative and interprets it in specifically literary terms. It would seem, then, that simply chopping out Verne’s meticulously researched detail distorts a key aspect of his identity as a novelist. (Indeed, the notorious Mercier version of Twenty Thousand Leagues also offers examples of translation howlers: for instance, he has Aronnax returning from ‘the disagreeable territory of Nebraska’ – which should be ‘the badlands of Nebraska’.)

Arthur B Evans also criticises ‘a more sinister type of inaccuracy’ in many English translations – namely ‘ideological censorship’. At least some translators seem to have modified Verne to suit the presumed tastes or morals of their target audience. ‘Many (or even most) early English translations of Verne’s novels…were systematically “purged” of any anti-British references,’ Evans notes. And in Henry Frith’s 1878 translation of Le Tour du monde en quatrevingts jours (Around the World in Eighty Days), Alex Kirstukas notes the omission of any passage that ‘could be construed as the slightest critique of the British Empire and its policies’. In other ideological shifts, translators have opted for euphemisms in place of Verne’s straightforward language, and offensive racial epithets instead of the author’s non-pejorative terms.

Verne scholars have also highlighted ways in which translations have dealt poorly with his humour, irony and wordplay. But the poor quality of so many of the English translations certainly did not prevent Verne’s novels from becoming enormously popular in the anglophone world, and inspiring everything from Hollywood movies to steampunk. It did, however, affect his reception as a writer, diminishing his literary reputation in a manner that would take decades to repair.

Revival and retranslation: time to revisit the texts

It was not until the 1960s that literary critics in the English-speaking world began to look at Verne with fresh eyes, thanks to the pioneering work of American literary critic and translator Walter James Miller. Miller realised that there was a massive discrepancy between the Verne of popular imagination and the original. He identified the problem of the ‘two Jules Vernes’: the ‘children’s author’ disparaged by American critics and science fiction writers – the product of abridged and flawed translations – and the more respected and scientifically accurate ‘European’ Verne. With his four landmark annotated translations, Miller is credited with kickstarting the serious academic study of Verne in the anglophone world and the reassessment of his importance as a writer.

The result is often referred to as the Verne ‘renaissance’ or ‘revival’ – a surge of fresh interest in the author’s works, including the translation of novels previously unavailable in English, and a gradual rehabilitation of his reputation among English readers. ‘English-language readers are now witnessing a veritable renaissance of interest in all things Vernian,’ says Arthur B Evans. ‘If this trend continues, the 21st century promises to be very kind indeed to the legendary yet often misunderstood author of the Voyages extraordinaires.’

Numerous new translations, as well as academic studies, have appeared in the last 50 years or so. With so many better translations now available, it is to be hoped that publishers will become more discerning and stop reissuing the abridged, flawed translations that have so distorted Verne’s literary identity. And yet it’s a testament to Verne’s imagination and storytelling skill that his novels proved so popular in the English-speaking world in spite of the shortcomings of the English translations. From Antarctica to the moon, from the depths of the earth to the submerged ruins of Atlantis, Verne takes us on voyages of discovery and imagination. Now English readers have better opportunities than ever before to discover his authentic voice.

Discover the Verne revival for yourself...

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas / A Journey to the Center of the Earth / Around the World in Eighty Days: William Butcher (Oxford World’s Classics), Frederick Paul Walter (in Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics, State University of New York)

- The Mysterious Island: Sidney Kravitz (Wesleyan University Press), Jordan Stump (Modern Library Classics)

- Circling The Moon: Frederick Paul Walter (in Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics, State University of New York)

- From the Earth to the Moon: Walter James Miller (Gramercy), Frederick Paul Walter (in Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics, State University of New York)

- Five Weeks in a Balloon: Frederick Paul Walter (Early Classics of Science Fiction)

- The Earth Turned Upside Down (Sans dessus dessous): Sophie Lewis (Hesperus Press)

- The Adventures of Captain Hatteras: William Butcher (Oxford World’s Classics)

- The Meteor Hunt: Frederick Paul Walter (University of Nebraska Press)

- The Castle in Transylvania (Le Château des Carpathes): Charlotte Mandell (Melville House)

About the writer

Gillian Robin MITI is a German to English translator with a special interest in science communication, the environment, nutrition and healthy living. She has a fascination with 19th-century science and society.

Never miss another Bulletin article

If you would like to read more features and articles on a wide variety of subjects relating to all aspects of the translation and interpreting industry, subscribe to ITI Bulletin. Alternatively, join ITI and get a free subscription included in your membership.