The translator’s kitchen diaries

Written by Hannah Lawrence

From clafoutis to cocktails, piperade to patisserie: Hannah Lawrence has just finished a year of cooking and translating one recipe a week. How has it gone?

That Translator Can Cook was a year-long translation, cooking and blogging challenge. Every week for a year, I selected a French recipe to translate and follow before blogging about the process. I discussed the translation and the cooking: the challenges, mishaps, workarounds and triumphs.

Beetroot verrines: a term that’s not familiar to the average English-speaking eater.

I came up with the idea in August 2019. Having just handed in the final project for my translation master’s, I’d launched myself into freelance translation. I’d begun contacting various agencies, joining industry bodies and network groups, and setting up my professional online presence. But I was aware that the translation marketplace was competitive, with some agencies unwilling to take a chance on a newly minted translator, and others receiving piles of applications. I needed some way to stand out from the crowd. I was also trying to decide which areas I wanted to specialise in and had started to think food and drink might be a good option, since I’ve long been interested in food and even maintained a travel and food blog for a little while. But I had no professional translation experience in this area.

It started with a clafoutis

One day I thought to myself: ‘Well, even if no one is paying you to do this type of work, you can just do it.’ This way, I’d start to learn more food-related French vocabulary, become more familiar with the sector, and populate my CAT tool. Slowly, the idea of the challenge started to form. I jumped on Twitter and the ITI French Network forum to explain my idea and ask for suggestions for a hashtag and challenge name. The response was overwhelming. Many thought it was an excellent idea. Some wanted to take part as well. And suggestions flowed in too. I was even pointed in the direction of a similar challenge, #Write52, which at least one other translator was embarking on.

The enthusiasm from my colleagues encouraged me to strike while the iron was hot. I quickly set up a website to house my blog. And before I knew it, come 6 September 2019, I’d published my first post of the challenge, on a cherry clafoutis.

The cherry clafoutis where it all began.

That same week, Emily Safrin, a Spanish to English translator in the United States, published her first #ThatTranslatorCanCook post, and others in the UK, France and Spain soon followed suit. It was great to have others joining in. In total, over eight translators have taken part off and on. Many put their own spin on the challenge. And a few are still going on with it. For instance, there’s Jennifer Case, an Arabic to English translator, who includes the translations of her recipes in her posts, although she doesn’t cook every single one because she has several allergies. There’s Stephanie Martinez-Hill, a French and Spanish to English translator, who’s produced some simply stunning bakes, along with accompanying videos. Meanwhile, in one of her posts, Arabic and French to English translator Verity Roat discussed and baked a French recipe for the traditional British Victoria sponge.

It’s now over 12 months later, and I’m proud to say I didn’t miss a week. I translated 51 recipes, totalling over 14,000 words, and penned a post halfway through about what makes the perfect cookbook. I prepared 49 recipes, welcoming a guest cook for the other two. I tried all sorts: from a classic French baguette to a Moroccan aubergine salad called zâalouk; from the citrusy French 75 cocktail to the refreshing poisson cru (a Tahitian raw fish and coconut milk dish).

Fine-tuning for my audience

I defined my target audience as the average British home cook. So although the recipes themselves tended to be short, I never struggled for topics to discuss in my blog posts. There was always some troublesome ingredient, some culturally specific reference or source-target culture difference to contend with.

A few recipes in, I noticed some common themes. The first was tricky ingredients. Understandably, recipes from mainland France generally feature ingredients that are familiar and readily available in France. And while many of the same ingredients are available here in the UK, this isn’t always the case. In some instances, I wasn’t familiar with an ingredient and had to do a bit of digging. One example was piment d’Espelette, (‘Espelette pepper’), which cropped up a couple of times, starting with the Basque piperade. Once I’d figured out what it was, I considered whether it was easily available for my target audience. Since it wasn’t, I tracked down a suitable alternative, adding this as an option in parentheses. For piperade, this came out as ‘Espelette pepper (or hot paprika)’.

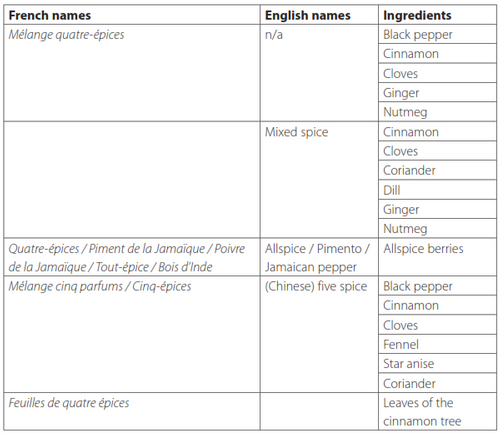

Another spice-related difficulty was quatre-épices, used in pain d’épices, or French spiced loaf. I started by trying to find out what the spice was. This led me down a rabbit warren of websites, trying to understand the difference between several similarly named spices and spice mixes. I even ended up putting together the table on the right to map out the differences.

Culinary knowledge (or not)

Another translation issue was over the names of the recipes themselves. In the UK, recipe names tend to be descriptive. They hint at a dish’s flavour, origins or method of cooking. They aim to tantalise and tempt, and tease you into trying them. French recipes don’t do this, which means that, when you are translating them for English-language audiences, you may need to get creative. For example, I renamed lentilles de Puy (‘Puy lentils’) as country lentil stew so that my target audience would understand the type of dish it was. Another recipe name that was difficult to translate was cake aux tomates séchées. The main problem here is that this is not a ‘cake’ as the British know it. It’s savoury and rectangular. In the end, I opted for ‘savoury sun-dried tomato loaf’.Then there was chronology. Instructions in English-language recipes tend to be listed in the order you need to complete them. Many French recipes seem less strict about this. For instance, the instruction to ‘add the beetroot, previously boiled, strained and cooled’ might appear halfway through a recipe, with no mention of cooking the beetroot up until that point. For a cook, this means you really need to read the whole recipe all the way through thoroughly – probably more than once – so that you know what you need to do when. As a translator, it puts you in quite a pickle. My preference is to change the order of the instructions so they’re sequential and reflect the target reader’s expectations. But if, like me, you’re using a CAT tool, this can have implications for your translation memory. I recently discussed this problem with some colleagues on Twitter, who suggested it might be best to reorder the text.

The classic culinary glory that is hollandaise sauce.

French recipes also often provide less detail than ones in English. One theory is that this is because French cooks are assumed to have a greater level of culinary knowledge than their British and other English-speaking counterparts so they don’t need it all spelled out; or you could put it another way, and say that English-language recipes make a greater effort to be accessible to beginner cooks. Another theory is that this is the result of a conscious decision to be less prescriptive, giving the French cook more freedom to make their own choices.

Whatever the rationale, I often expanded my translation to provide the expected level of detail for the target reader. If this were a paid job, it would of course be best to check this with the author or publisher. They might prefer to keep things minimal. Or they might want to give you more precise detail: what sort of temperature do they mean by ‘a hot oven’, for example?

An excellent example of this minimalism was in the recipe for speculaas biscuits. Here are translations of some instructions from the source recipe, compared to the sort that I would have expected to see in an English-language recipe – the bold sections indicate elements that didn’t appear in the source.

- n/a > Preheat the oven to 160°C.

- Roll the dough out thinly > Roll out the dough until 5 mm thick.

- Bake for 15 minutes at a low temperature > Bake for 15 minutes or until golden.

I considered the ingredients and the typical challenges of a soufflé (that it sinks) and decided that ‘fold’ was indeed the right term to use.

A (very odd) year of learning

When I started, of course, I had no idea what would happen part-way through the challenge. With lockdown came shortages, and certain ingredients like flour and eggs became hard to find. It was clearly a difficult time for so many, and it made my own self-imposed challenge seem insignificant and frivolous. But I was far too stubborn to give up after so many weeks. And I thought it might prove a nice distraction from the doom and gloom. So I kept going. But I did adapt. I chose less convoluted recipes with ingredients that were easier to come by. I added in a ‘recipe and substitution ideas’ section, where I shared existing recipes in English for the dish I’d cooked and included some ideas for ingredient swaps.

The international lockdown favourite: sourdough baguettes.

Over these 52 weeks, I’ve learned plenty of French culinary terms and ingredients – and some English ones. I’ve built up my translation memory and termbase. I’ve become familiar with the style of French recipes and identified how they differ from English equivalents. I’ve tried many new recipes and expanded my culinary repertoire. I’ve met many colleagues who translate in this area or just happen to love food. They’ve taught me a lot, from help with a tricky ingredient to demonstrating a different way of approaching food translation. So, thank you to Pili, Emily, Jennifer, K-Rae, Stephanie, Solène, Valérie and Verity, and the many others who’ve discussed, shared, and encouraged me.

Taking part in this challenge has also helped me grow my presence, network, and reputation within both translation and copywriting. For a start, it’s given me something to talk about at industry events and on social media. It’s driven traffic to my website and my LinkedIn profile and helped get my name out there. And this has in turn led to opportunities for work. In fact, I’ve gained regular clients – including in food translation – both directly and indirectly as a result of the challenge. So, has it been successful? Most definitely. Will I be going back for seconds? Not right away. But leave it a little while and I may be tempted. I’d also encourage others to consider some more out-there forms of continuing professional development. After all, what have you got to lose?

The year in numbers

14,000+ words translated

51 recipes translated

2,300+ website visits*

*unique page views on blog posts and webpages related to the challenge (Google Analytics).

This article appeared as the cover article in the November-December 2020 edition of the ITI Bulletin. Photos © Hannah Lawrence

About the writer

Hannah Lawrence is a freelance translator (French to English), copywriter and transcreator with a background in marketing. She particularly enjoys working on creative texts, and specialises in marketing, education, and food and drink. Originally from New Zealand, she’s been living in London since 2012. Find her on www.hannahtranslates.com, Twitter, or Instagram.

Never miss another Bulletin article

If you would like to read more features and articles on a wide variety of subjects relating to all aspects of the translation and interpreting industry, subscribe to ITI Bulletin. Alternatively, join ITI and get a free subscription included in your membership.