Words for a time of disaster

ITI’s Japanese network put out a call to its members to commemorate 10 years since the Tohoku earthquake. Wendy Uchimura looks back at what translators can do at times like this

Japan is used to earthquakes. And this one, on 11 March 2011, started out like any other: a gentle side-to-side swaying that rocked me on the sofa, and made me hope that it would lull my five-month-old son into his afternoon nap. Within 20 seconds, though, I realised this was something very different. It felt as if the wall behind me and the floor underneath were buckling and pushing me up, while the TV screen in front of me went ominously black. I dived under the dining table with my baby, sheltering him with my body, as the shaking intensified. The lurching increased; I could hear crashing above; and then the house started spiralling like a gyroscope.

I heard my own voice shouting ‘Stop! Stop now!’ Because if it didn’t, this was it.

After the first shake and aftershock

I don’t remember how the shaking ended, but the minute I felt it was safe to move I went into automatic mode. I desperately wanted to set straight off to get my four-year-old son, who was at day care over the hill, but I knew I had to wait. With a quake that big, an aftershock would come within the next 20 to 30 minutes, and it did. Then, finally, I could go into action with the baby in a pack on my chest, rucksack with snacks, emergency radio and water on my back, and at the last moment a large umbrella (I think I planned to use it to steady my way like a walking stick if necessary).

Down near the train station, the only indication of any sense of disaster was a woman cycling past with a big pack of toilet rolls. A little further on I saw a packed bus; the trains had stopped running. Because I was out, I wasn’t watching the live TV footage but I know now what it showed: the black waters rushing in, rising, unceasing, washing away houses, cars and buildings; the cries of the people as they watched in the terrifying knowledge that lives were being mercilessly swept away; the shouts of ‘Yamete’ (‘stop’) echoing what I’d shouted at the earthquake in vain.

A message came in on my phone from my husband at work in Tokyo saying he was fine. I sent a very short message to my family back in the UK: ‘We’re all OK.’ It was a good thing I did. After that the network service dropped out: all broadband was now being dedicated to the emergency services. My husband was finally able to get home at 2am the next day. He and his work colleagues spent nine hours on a journey that should have taken 50 minutes. They’d had to quickly evacuate their office and go out onto the street during the earthquake because cracks had started appearing in the walls.

The first quake was over. I didn’t know that the earth would continue shaking for months.

Quake, tsunami and aftershocks

Over the next few days, power became a limited resource, with rolling blackouts and pleas from the TV to conserve electricity and switch off anything we could. The government officials all changed their black business suits to blue work overalls. We were in the time of disaster, and it wasn’t stopping. First the quake, then the tsunami, and the relentless aftershocks. We slept in the living room huddled together on futons, so that whenever there was a large shake in the night, we could switch the TV on straight away to find out what was happening and all get out together as quickly as possible if needed. The news showed us the ever-rising figures of the missing and dead, reports of damage to buildings and infrastructure, even worrying reports that Mt Fuji was becoming active. By 16 March, it had also become clear that the damage at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was in itself a major disaster. I felt helpless, but desperately wanted to help in some way.

But what could a translator do to help at such a time?

In my case, the answer came that same day. A call went out in a Facebook group about an American teacher, Taylor Anderson, who was missing in Ishinomaki. Her friends needed help to find her. Translation help.

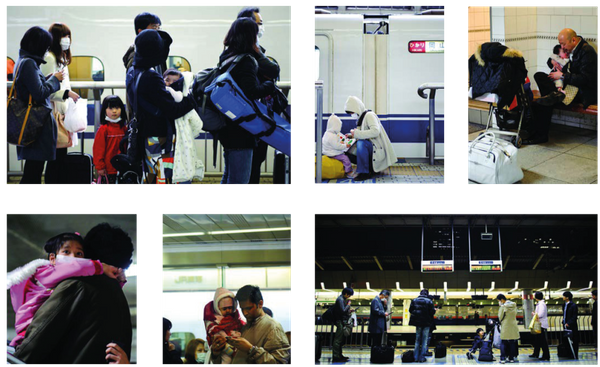

'By that point there was a febrile, fearful atmosphere in Tokyo, as if panic was about to take hold’: leavers start to queue for the bullet train

An endless search to find names of survivors

As part of Google Person Finder, a Picasa account had been set up so that photos of the handwritten lists of survivors’ names at the growing number of evacuation centres could be uploaded, viewed and entered on a database. We focused on the lists coming out of Ishinomaki to search for Taylor’s name in katakana (a Japanese writing system used to transcribe non-Japanese names) and to find out which evacuation centre she could be at. Looking through, we found quite a few katakana names. If they were entered into Person Finder in a Japanese script, people from overseas who were worried about their loved ones would not be able to find that crucial information. So along with searching for Taylor’s name, we also began checking that these other names were also entered in roman script.

We searched through up to 100 photos a day. The first priority was of course to find Taylor’s name. Once we’d confirmed it wasn’t there, we then went through the database checking the other katakana names. After guessing the approximate roman alphabet spelling, we then checked if there was already an existing entry. Sometimes there were duplicate entries for the same person because the same name had been transliterated slightly differently by several people. Sometimes there were already entries created by loved ones searching for them: each entry not just a name, but an individual story. And every day the lists changed, as more and more new people arrived at the evacuation centres.

My recollection from the time: I find a name, transliterate it as best I can, search for a matching entry. There it is. A family member is searching for her. She’s a mother who’d been travelling with her two children in the area. They haven’t heard from her. They want to know she’s safe. I look back at the image I’m working on. A couple of entries down, I see someone with the same surname. I scan on to the end, then back and forth through all the updates for that centre, then back again. I have to accept. The other child’s name is not there.

On 21 March, our group received the sad news that Taylor’s body had been found. Some of us continued into the next week checking other names, but as the number of new images being updated began to dwindle – down to one photo a day at most centres – it became painfully obvious there would be no more survivors. Around that time, I went out on my balcony and saw my first ever bluebottle fly in Japan. I knew what it meant.

More translation to support disaster relief

Since I’d become familiar with this type of online translating and databasing, in April I joined a Japanese volunteer Facebook group helping translate the essential relief activity information needed for volunteers going into the disaster area. Everyone had an overwhelming desire to help, but unfortunately some well-meaning volunteers were turning up unprepared, expecting to be able to find somewhere to sleep and food to eat. The reality was they needed to be completely self-reliant because there was very little there and all resources needed to go to the disaster victims. Some also had preconceived ideas of how they were going to help, which in practice just contributed to further distress rather than bringing relief.

Deaf and hard-of-hearing people had sadly been particularly hard hit. Many of us who went through this disaster will remember how the first few weeks after the earthquake were filled with constant noise. Alarms, alerts and sirens blared out day and night from phones, TVs, public tannoys…and soon afterwards the ground would start shaking again. Deaf and hard-of-hearing people had no access to this information.

To make matters worse, it very soon became clear that few local government workers were able to use Japanese sign language. Some deaf people moved out of the evacuation centres back to their own damaged houses because it was too stressful not being able to communicate their needs properly. And although they were registered with the local authorities as being disabled, privacy laws meant their information could not be shared with the volunteer groups that could give them access to the support they needed. So as time went on, the content of my translation work shifted from status reports of vulnerable communities in the disaster area to initiatives that would ensure inclusivity and accessibility in disaster planning.

Our office life changed too. We were all given flame-resistant silver emergency bags to place under our desks, along with white hard hats and steel-toecap boots. Regular training was carried out, coordinated with the local fire station so that they could check we were all fully equipped and could evacuate the building within the required time frame. Rather than getting over the disaster, we were learning in a practical sense to both live with it and be prepared for it. But psychologically…

My recollection from the time: I’m sitting at my desk facing the window when the office building lurches, revealing more of the street below than I’m happy with.

The woman next to me, just transferred from Osaka, looks concerned, but I notice she’s shifting her gaze around the room to each of us. She’s concerned about us.

‘You all have PTSD,’ she observes.

She’s right.

The quake, now over, had not been that big, maybe a Shindo 3, and very short. Before March 2011, it would have got a few calmly whispered ‘Aa, jishin da’ [‘Ah, an earthquake’].

But now here I am, hand on silver emergency bag ready to take flight, another colleague frozen in place, over there someone gripping their desk white-knuckled as if it could be ripped out from beneath them.

It’s difficult to imagine if one day an earthquake can ever just be an earthquake again.

The body remembers and so does the mind

I started drafting this article at the start of February 2021 and immediately found myself struggling to recall the events, because my subconscious didn’t want to remember. I couldn’t bring myself to watch footage of the time to jog my memory, and tracing back to the messages and comments I made during the initial few months was painful.

Then on 13 February a big earthquake jolted me. It felt very similar to the Tohoku earthquake of 11 March 2011 (in fact it was later identified as an aftershock of the Tohoku one 10 years ago). Starting with soft swaying, it shifted to large jerks until that very recognisable, unforgettable spiralling motion set in. This time, we were separated over the three floors of our house: us in the downstairs bedroom, awake, waiting out the tremors; my younger son, who surprisingly slept right through it, on the first floor; and my older son, who woke but stayed calm, on the second floor.

After the Tohoku quake, I messaged my immediate family: ‘We’re all OK.’

This time, nearly 10 years later, I asked everyone I know: ‘Are we all OK?’

This article appeared as the cover article in the July-August 2021 issue of the ITI Bulletin. A full original version of this article was published in the J-Net Bulletin: 10 Years of Tohoku Earthquake special issue along with other articles by members

About the writers

Wendy Uchimura is originally from Yorkshire, England, but is currently based in Yokohama, Japan. She specialises in the legal (copyrights, design, trademarks) and licensing fields, although she has often been known to stray into marketing, popular Japanese culture, and arts translation.

A former journalist, Tony McNicol is a qualified member of ITI with over 10 years’ experience as a translator. After living in Japan for 15 years, in 2013 he returned to the UK and set up a specialist Japanese translation agency, WeDoJapan Ltd, with his wife Yoshie Harimoto. They work in the fields of marketing, media, hospitality, tourism and more. Tony is the translator of three personal development non-fiction books, including Shinrin-yoku by Yoshifumi Miyazaki (Octopus, 2018). He has also worked on subtitling and translation for broadcasters such as NHK, the BBC and History Channel.

Never miss another Bulletin article

If you would like to read more features and articles on a wide variety of subjects relating to all aspects of the translation and interpreting industry, subscribe to ITI Bulletin. Alternatively, join ITI and get a free subscription included in your membership.